Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS | More

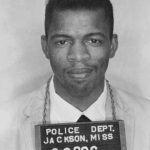

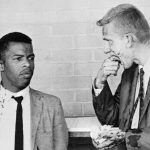

Image Credit: The Guardian

John Robert Lewis was born on February 21, 1940, in Pike County, Alabama. As he learned during a filming of Finding Your Roots, his great-great-grandfather, Tobias Carter, registered to voted in 1867, 2 years after the abolition of slavery. But almost 100 years later, Lewis, his sharecropper parents, and thousands of other descendants of enslaved people were prevented from voting.

Inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Montgomery bus boycott, Lewis organized non-violent protests such as sit-ins, and joined the 1961 Freedom Rides. He assumed leadership of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1963. In ’64, SNCC and other civil rights groups led an effort to educate African Americans in Mississippi, and register them to vote. Reflecting on it in 1985, Lewis wrote,

“The Mississippi Freedom Summer was an attempt to bring the nation to Mississippi, to open up the state and the South and bring the dirt of racism and violence from under the rug so all of America could see and deal with it …

During the summer many churches were bombed and burned, particularly black churches in small towns and rural communities that had been headquarters for Freedom Schools and for voter registration rallies. There was shooting at homes; we lived with constant fear. We felt that we were part of a nonviolent army, and in the group you had a sense of solidarity, and you knew you had to move on in spite of your fear.”

Lewis’s advocacy for the disenfranchised, marginalized, and oppressed continued beyond Freedom Summer into the rest of his life. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives (GA-5) in November, 1986. His numerous awards include the Medal of Freedom, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Non-Violent Peace Prize, and the John F. Kennedy “Profile in Courage Award” for Lifetime Achievement. Congressman Lewis died Friday, July 17, 2020.

This episode was originally posted on September 7, 2019.

Many letters and narratives in this series were read with permission from the Wisconsin Historical Society and the University of Southern Mississippi. The letters of Cephas Hughes are accessible via the Miami University Libraries Walter Havighurst Special Collections and University Archives.

The following sources were also used:

Finding Your Roots: John Lewis and Cory Booker

Freedom Summer, Mississippi 1964, snccdigital.org

Freedom Summer: The 1964 Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi, Susan Goldman Rubin

Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC

Letters from Mississippi, Elizabeth Sutherland Martinez

Mississippi Freedom Summer–20 Years Later, Dissent Magazine

Mississippi Freedom Summer Events, Civil Rights Movement Veterans