Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS | More

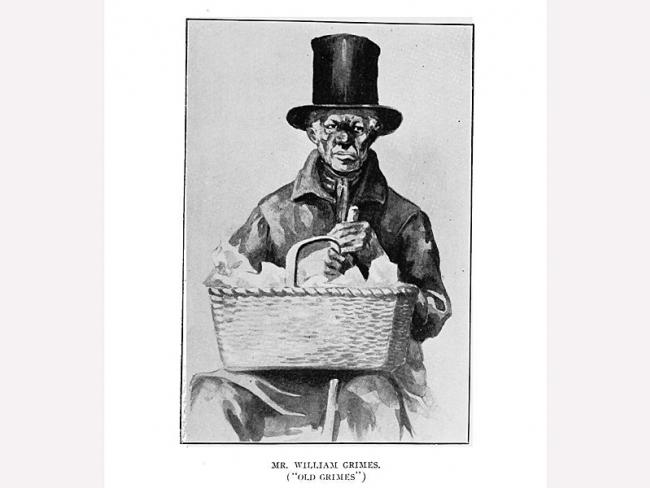

Image credit: Library of Congress

“My first work in the mines was at Borderland, WV, and I was 13 years old. Back then, people think now, when you say you were 13 years old and start in the mines, they think something funny about it. Back then, there was no such thing as a social security card. All you had to do was be big enough to do a days work. I went to helping my Daddy on the track and I was kind of thin and he told me to put on extra pair of pants and on an extra shirt to look big and we worked on the outside the first day I started to work. I got hot and started shedding the pants and shirt.” — Frank Brooks, Retired Coal Miner at age 71, 1973

The West Virginia Mine Wars were violent conflicts between mine workers and mine owners, that took place between 1912 and 1922. In all there were five armed battles over that 10-year period:

Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike

Battle of Matewan

Battle of Tug

Miners’ March on Logan

Battle of Blair Mountain

One violent exchange took place on February 7, 1913, during the Paint Creek battle. Coal operator Quin Morton and Kanawha County Sherriff Bonner Hill rode an armored train through a miner’s tent colony at Paint Creek. Guards opened fire from the train and killed Cesco Estep, one of the miners on strike. Later, miners attacked an encampment of mine guards. In the ensuing battle at least 16 people, mostly mine guards, were killed.

This first episode in a three-part series focuses on the history of the mining industry, and the conditions that led up to the Mine Wars.

I referred to several sources, including the following–

Black Coal Miners in America: Race, Class, and Community Conflict, 1780-1980, by Ronald L. Lewis

Oral History Interview: Frank Brooks

West Virginia Archives and History

Written in Blood: Courage and Corruption in the Appalachian War of Extraction, edited by Wess Harris

Women of the Army Signal Corps at First Army Headquarters

Women of the Army Signal Corps at First Army Headquarters