Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS | More

[/audio]

November 4, 1918

The chauffeurs have been most tremendously busy these last two weeks on account of moving. My life seems to hinge around choked carbureters, broken springs, long hours on the road, food snatched when you can get it, and sleep. Nothing else has mattered to me and I feel like a regular camion driver, dirty, but so accustomed to the job that it is no longer tiring.

…

The country over which I have been motoring is tremendously interesting, but most gloomy; unless there are soldiers about there is not a living thing, nothing but waste and destruction. If you saw a whole house you would stop and look at it as a phenomenon. One evening I tried to take a shortcut home with a doctor and we got most hopelessly involved in bad roads which finally led us to an impassable bridge.

We had to retrace our steps completely and start all over again … Never again will I be so foolish as to try short cuts home through ” No Man’s Land,” even if it is French property now.

–Letter from Nora Saltonstall

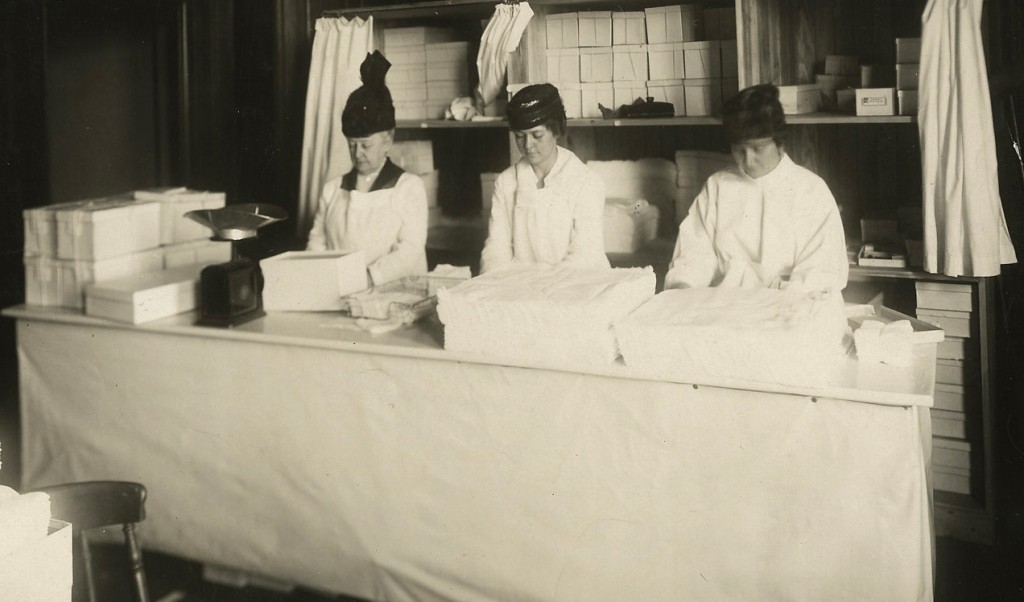

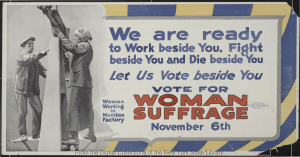

The fighting stopped on 11/11 at 11 a.m. But the needs continued. In the aftermath of World War I, among the rubble and ruin, American women continued to serve. Significant relief was provided by the American Fund for French Wounded (AFFW) and the Comité Américain pour les Régions Dévastées de France (CARD). Women like Anne Tracy Morgan used their wealth and social status to help the French rebuild their homes and villages long after the Treaty of Versailles was signed.

Recommended Reading:

America’s Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines, Gail Collins

Into the Breach, American Women Overseas in World War I, Dorothy and Carl Schneider

Credits for Primary Sources:

Letters of Laura Birkhead, read with permission from the State Historical Society of Missouri

Letters of Marian Bartol, managed by the Morgan Library and Museum

The overseas war record of the Winsor school, 1914-1919, (Elizabeth Beal, Amy Bradley, Isabel Coolidge, Nora Saltonstall)