Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS | More

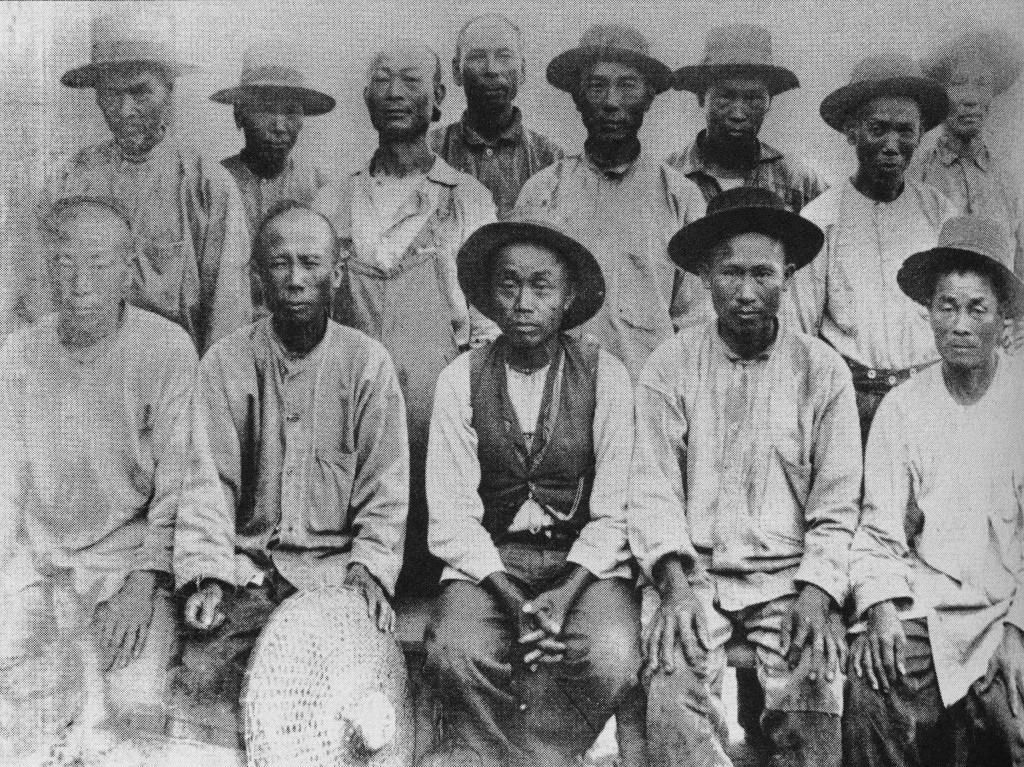

(Library of Congress)

“You have expended a lot of the Public money foolishly, all because of a one poor little Child. Her playmates is all Caucasians, ever since she could toddle around. If she is good enough to play with them! Then is she not good enough to be in the same room and studie with them? You had better come and see for yourselves. See if the Tape’s is not same as other Caucasians, except in features. It seems no matter how a Chinese may live and dress so long as you know they Chinese. Then they are hated as one. There is not any right or justice for them.”

–Mary Tape

Among the many young girls who arrived in San Francisco in 1868, was one 11-year-old from Shanghai. After five months in Chinatown, she was taken in by Ladies’ Protection and Relief Society on Franklin Street, where she was given the name Mary.

The following year, Chew Diep arrived from Taishan. In 1875, he met Mary while he delivered milk for the Sterling family. They married on November 16, and before long, Chew Diep changed his name to Joe Tape. The Tapes’ daughter Mamie was born the following summer. The Tapes would have three more children: Frank, Emily, and Gertrude.

The Tapes lived in the Black Point neighborhood, now called Cow Hollow, which was predominantly white. Teen neighbor Florence Eveleth taught little Mamie and Frank reading and math. But neither the Tapes’ affluence nor assimilation could protect them from discrimination.

Additional Resources:

“The 8-Year-Old Chinese-American Girl Who Helped Desegregate Schools” (History Channel)

“Before Brown v. Board of Education, There was Tape v. Hurley” (Library of Congress)

“In Pursuit of Equality: Separate is Not Equal” (Smithsonian Museum of Natural History)

The Lucky Ones: One Family and the Extraordinary Invention of Chinese America by Mae Ngai

“The Tapes of Russell Street” (Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association)

Unbound Voices: Chinese Women in San Francisco by Judy Yung

“We Have Always Lived as Americans” (The New York Historical Society)

“What a Chinese Girl Did,” The Morning Call, November 23, 1892, Page 12